Breaking the Ice: Polar Science on the SOS Voyage

We invited Professor Helen Amanda Fricker and Dr. Bryony Freer from the Scripps Polar Center to contribute this blog post following their powerful engagement with the SOS community — both on stage at the SOS Ocean Summit and during the SOS Ocean Voyage from San Francisco to San Diego.

Helen and Bryony are internationally recognized glaciologists whose research sits at the heart of one of the defining challenges of our time: understanding how rapidly melting ice sheets shape global sea-level rise, climate risk, and coastal resilience. Their work provides the scientific foundation needed for policymakers, innovators, investors, and communities to make informed decisions — exactly the kind of knowledge SOS aims to bridge into action.

Part 1: Reflections

Helen Amanda Fricker & Bryony Freer, Scripps Polar Center

Solving some of the biggest challenges facing society today requires

something beyond incremental progress or siloed expertise. They demand energetic teams that cross boundaries, new ways of thinking, and collaborations that don’t fit neatly into any one discipline. Perhaps our biggest societal challenge is that the Earth system is warming rapidly, leading to intensified weather extremes, storms, floods, wildfires and sea level rise. If humanity and biodiversity are to thrive on a planet experiencing so much change, we need better data, better models, and better solutions to help us manage our resources and ensure resilience. And that requires scientists, entrepreneurs, policymakers, technologists, educators, storytellers, and community voices working together.

Yet those connections don’t happen easily. Our scientific conferences are rewarding and fruitful, but can become echo chambers; we talk mostly to people who think like we do, publish in the same journals, use the same jargon. Our work doesn’t always get communicated in a way that it reaches the people who could use it – or challenge it – in transformative ways. Sometimes the most meaningful collaborations happen only when we step outside the spaces we know, and accept opportunities that stretch us beyond our comfort zones, to the edges of our own knowledge and expertise.

We recently did exactly that, when we boarded the Norwegian tall ship S/S Statsraad Lehmkuhl for a voyage from San Francisco to San Diego, hosted by Sustainable Oceans Solutions (SOS). Our familiar world of ice sheets and satellite altimetry gave way to days standing watch under the stars, hauling lines alongside shipmates, and sleeping shoulder-to shoulder-in hammocks.

Our shipmates represented expertise different to that of our science colleagues: venture capitalists, startup founders, engineers, writers; people shaped by industry and invention rather than academia. On the S/S Lehmkuhl there was no hierarchy between the passengers – no titles, no disciplinary walls. Working the deck together forced us to slow down, listen, and see the ocean – and each other – through an entirely new perspective. Over the course of the S/S Lehmkuhl voyage, we attended thought-provoking workshops, wrestled with ideas, learned from people whose expertise sits far from our own, and discovered unexpected overlap in the questions that drive us. We also had the chance to share our own research with our fellow shipmates – speaking about the increasing impact of melting ice sheets and glaciers on global sea level rise, and what needs to be done (and not done – looking at you, geoengineering) to slow the pace of change. We’ve included a short summary of that talk below for anyone interested in the details.

The experience was a powerful reminder that the future of ocean and climate solutions won’t come from any one field, but from work that straddles the boundaries where disciplines meet, collide, and create something new. We are so grateful to the officers and crew of the S/S Statsraad Lehmkuhl, and to Johan and Kristin Odfjell and the entire SOS team for inviting us to take part in this incredible voyage.

Part 2:

Understanding Sea-Level Rise:

What’s Driving It and What We Must Do

The Earth system is warming rapidly.

NASA scientists reported that 2024 was the warmest year on record, with global temperatures 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit (1.3 degrees Celsius) above the 20th-century baseline (1951-1980).

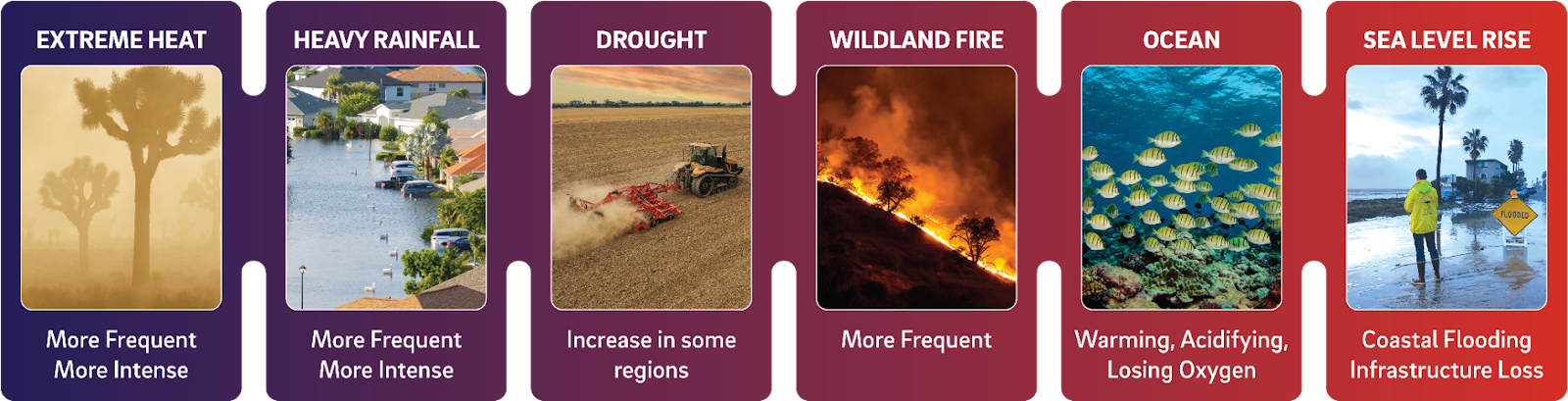

Climate change has led to new extremes.

“As the climate changes, the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events are increasing” - Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Report 6 (AR6)

Heavy rainfall, extreme heat, wildland fire, and drought events are becoming more frequent and more intense around the world. The ocean is warming and acidifying, and sea levels are rising, leading to more frequent and extreme coastal flooding events, damaging infrastructure in many low-lying coastal communities. Many factors are contributing to rising seas, and our work as glaciologists is focused on understanding how much the melting of the world’s land ice – glaciers, ice caps and ice sheets – is contributing to global sea level change.

Annual surface temperature anomalies between 1881 and 2024 relative to the 1951-1980 average. Higher than normal temperatures are shown in red and lower than normal temperatures are shown in blue. The final frame shows global temperature anomalies in 2024. [Credit: NASA's Scientific Visualization Studio. Data provided by Robert B. Schmunk (NASA/GSFC GISS)]

A visualization of global temperature anomalies (in degrees Celsius) relative to the 1850-1900 average, highlighting the record years of 2024, 2023, and 2016.

[Credit: Jennifer Matthews]

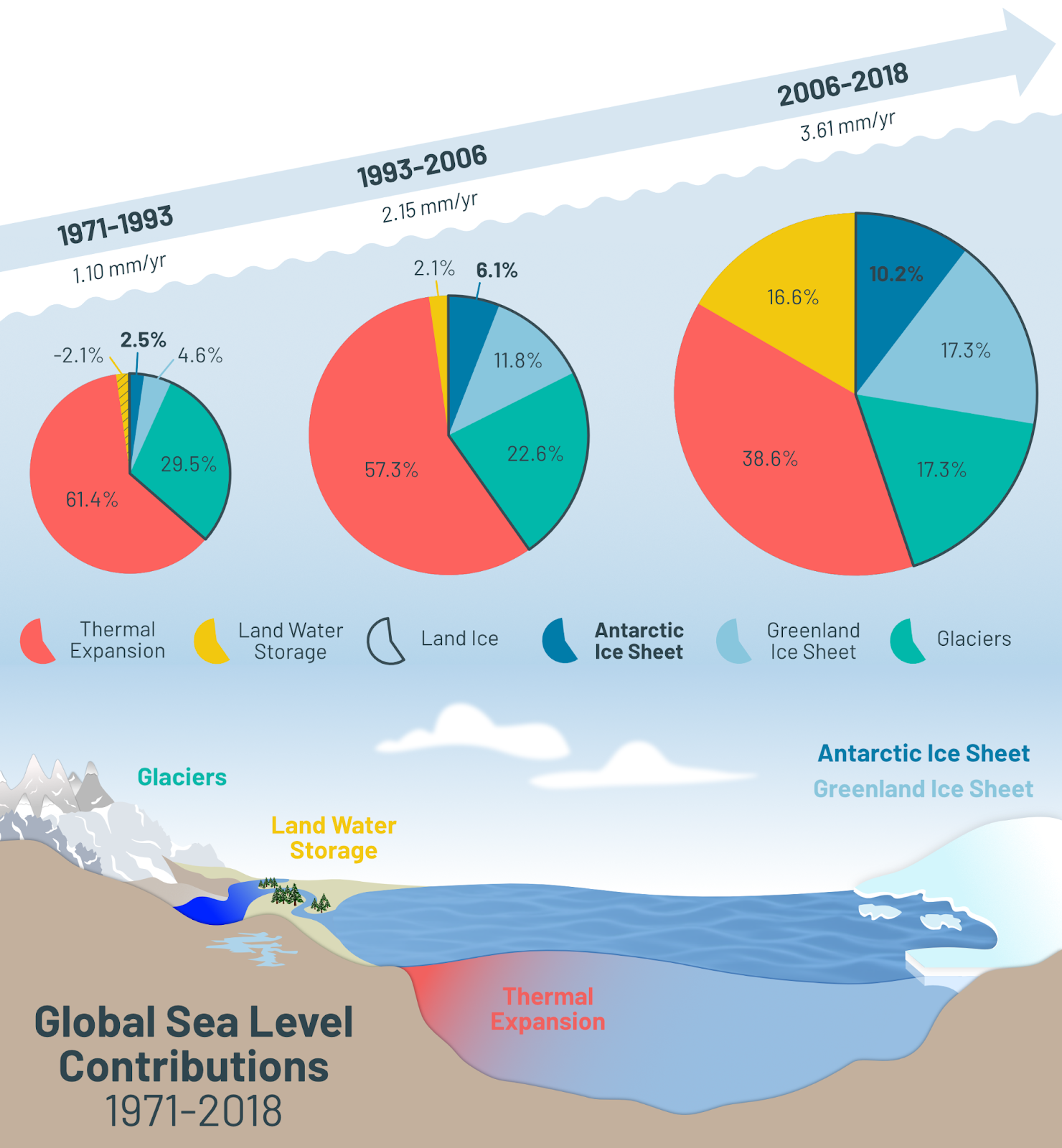

Warming oceans, melting ice, and the pumping of groundwater are the main drivers of global sea-level change. On the S/S Lehmkuhl, during our science stop offshore of the Channel Islands we used the CTD to measure water temperature and link those observations to one of the major contributors to sea-level rise: thermal expansion. When the ocean warms, the water expands and takes up more space, causing sea level to rise. Other contributors include changes in land-water storage and melt from glaciers and ice sheets, which is the focus of our research at the Scripps Polar Center.

The rate of global sea-level rise has been accelerating steadily since modern records began. Between 1971 and 1993, sea level increased by about 1.1 mm per year, and only around 7% of that rise came from melt of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. By 2006-2018, the rate of global sea-level rise had more than tripled to 3.6 mm per year. Over the same period, the contribution from ice-sheet melt had quadrupled, accounting for about 28% of total sea-level rise – roughly 10% from Antarctica and 17% from Greenland.

Caption: Change in the rate of global sea level rise over three periods: 1971-1993, 1993-2006, and 2006-2018, and the change in the relative contributions of thermal expansion (i.e. warmer water takes up more room), land water storage (lakes, rivers, groundwater aquifers), and melt from the world’s land ice reservoirs (glaciers and the Greenland + Antarctic ice sheets) [Credit: Bryony Freer. Data from IPCC AR6]

Melting ice has far-reaching consequences

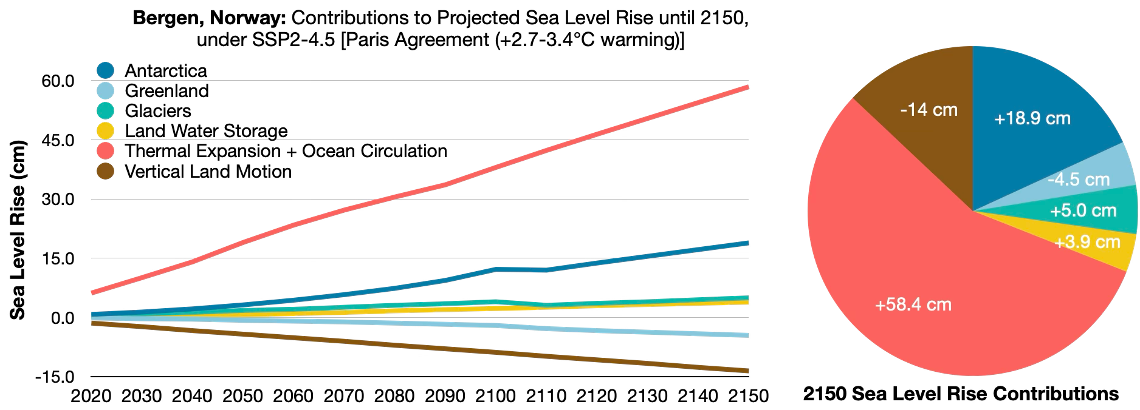

In Bergen, most of the sea-level rise over the coming century will come from two sources: the warming and expansion of ocean water, and melt from the Antarctic Ice Sheet, not from Greenland.

Under an intermediate, "middle of the road" climate scenario (SSP2-4.5) – where greenhouse gas emissions continue around current levels until 2050 before declining but do not reach net-zero by 2100 – Bergen is projected to experience 70 cm of sea level rise by 2150.

The contributions from Antarctica, ocean warming, melting glaciers, and changes in land-water storage will be partly offset by vertical land motion. The land around Bergen is still slowly rebounding after being pushed down by ice during the last ice age, which slightly reduces the amount of relative sea-level rise observed here. It may seem counter-intuitive, but Greenland’s melt will also actually slightly reduce sea level rise in Bergen. This is because, as the ice sheet melts and loses mass, its gravitational pull on the surrounding ocean weakens, causing water to shift away and sea levels near Greenland (including Norway) to fall.

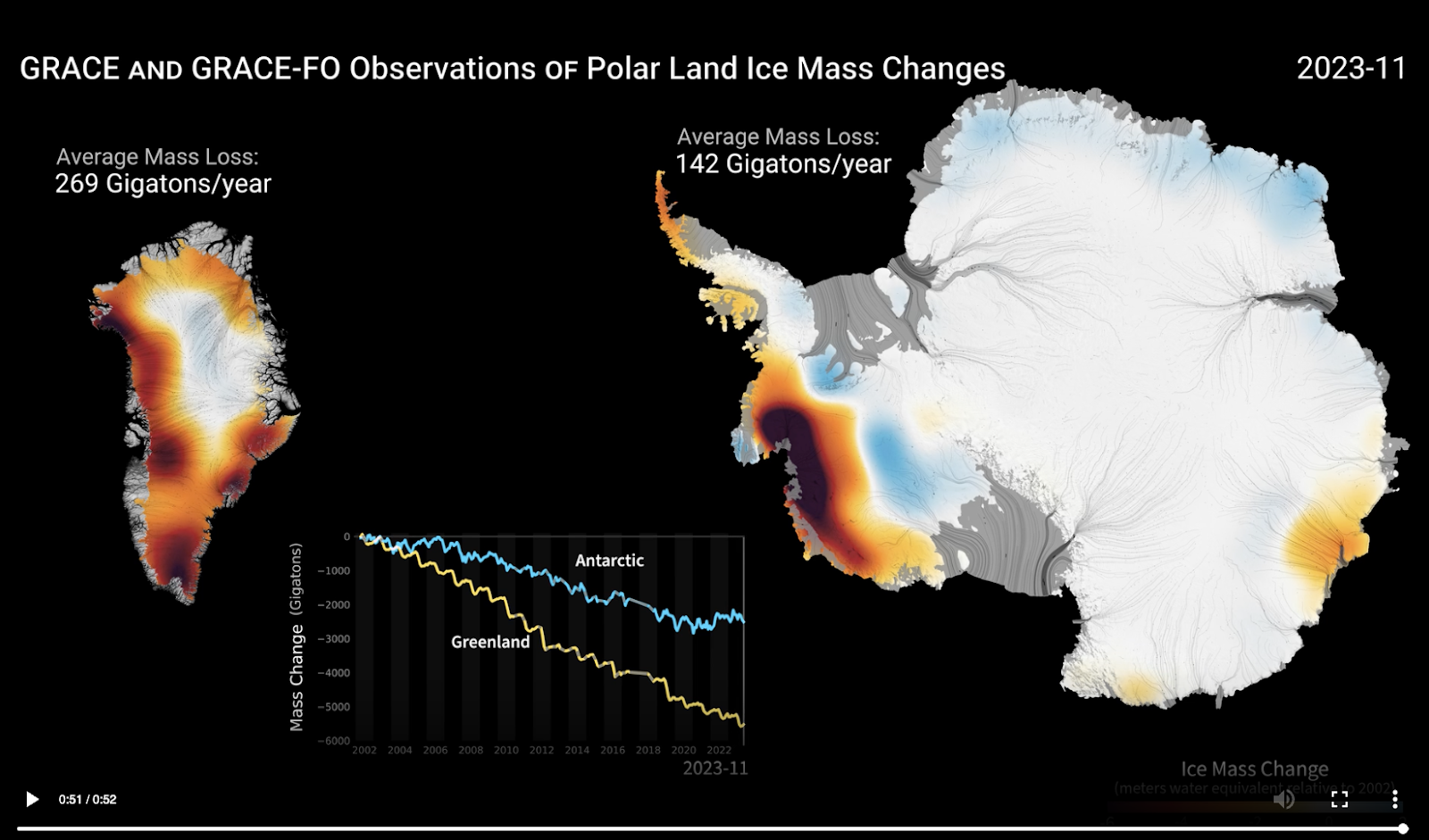

Ice sheets are the largest reservoirs of freshwater on the planet but are melting rapidly. This animation shows Antarctic and Greenland ice sheet mass losses between 2002 and 2023. The red areas are where we are losing ice mass; the blue areas are where we are gaining ice mass. [Video Credit: NASA and JPL/Caltech]. The areas losing the most mass in Antarctica are where the floating ice shelves are being melted from below by warmer ocean currents. The increase in mass in some areas (blue) is mainly driven by increased snowfall caused by a warming of the atmosphere.

{replace screenshot with Video 3, saved in Google Drive here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1IU9Ul8ecaaGgCZrb5z3JA-sY19hleWqk?usp=sharing }

Credit: NASA and JPL/Caltech

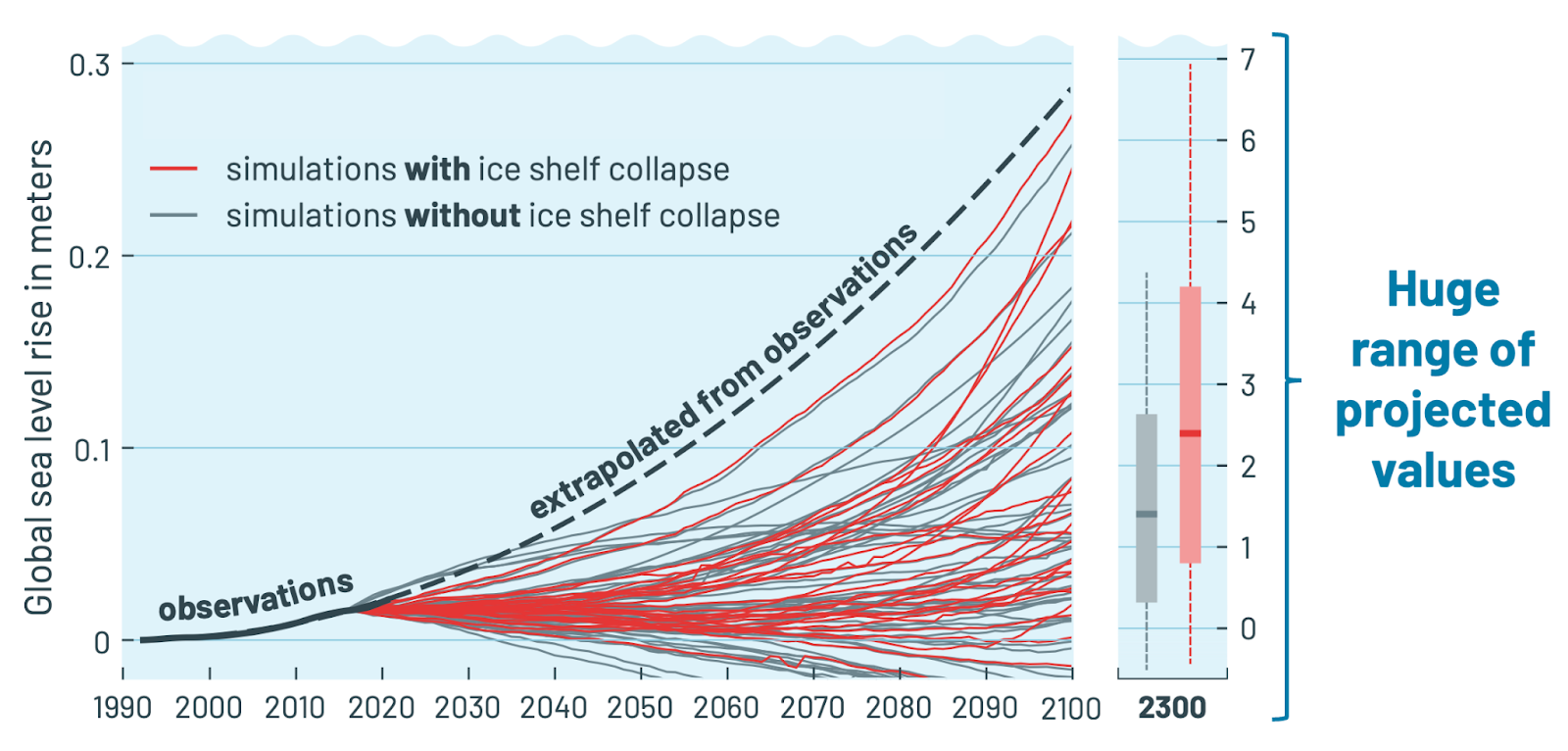

The future contribution of Antarctica to sea level rise is deeply uncertain. This figure shows the observed Antarctic Ice Sheet contribution to global sea level rise from 1992–2020, and the projected future contribution to 2100 and 2300. The wide spread in projected values highlights just how large this uncertainty is – driven by differences in emissions scenarios, ice-sheet model configurations, and our limited understanding of key processes such as ice-shelf collapse. The ocean melts the ice mostly around its edges, where the interactions are turbulent and complicated. But our observations are limited – both geographically and over time – and miss many of the key processes at dynamic ice margins, which reduces our ability to predict how the ice sheet will change in the future. Addressing these gaps is a core focus of our research at the Scripps Polar Center.

[Credit: Bryony Freer, adapted from Fricker et al. (2025) ]

So, what do we need to do?

At the Scripps Polar Center, our work focuses on improving the Antarctic Ice Sheet piece of the sea-level-rise puzzle. In the current political and economic climate, it’s more important than ever to focus investment on the areas that matter most (Figure X). To close the gaps in Antarctic sea-level-rise projections, we must continue to support the continuity and evolution of satellite missions (such as NISAR, CRISTAL, and EDGE), alongside targeted field campaigns and improved ice-sheet models. These tools allow us to observe the processes driving change and sharpen our projections of future sea-level rise.

Equally crucial is ensuring that this science is translated into actionable information that can guide policy, planning, and adaptation around the world. And we cannot overlook the importance of educating and inspiring the next generation of polar scientists. Yet, across all of these areas, funding and resources are shrinking.

At the same time, there is growing enthusiasm for untested geoengineering “solutions” in the polar regions. Proposals like installing massive underwater curtains beneath ice shelves to block warm water, or drilling into the ice sheet to pump water out from below, are extremely high-risk and face enormous challenges: access, logistics, technological feasibility, cost, environmental impacts, and governance. We see this trend as a diversion of critical resources and attention away from essential polar research – and, importantly, as a distraction from the fundamental task of global decarbonization. These ideas can create the dangerous illusion that a technological fix is around the corner, when in reality the most effective solution is cutting emissions.

For those working in or funding this space, we strongly encourage engaging with the glaciological community before pursuing any of these proposed technologies. Earlier this year, Helen was one of 42 scientific authors of a comprehensive review evaluating each of these geoengineering ideas – you can read that paper here.

For more information on Antarctica and sea level rise, please see:

Fricker, H. A., Freer, B. I. D., Galton-Fenzi, B. K., & Walker, C. C. (2025). Earth at 1.5 degrees warming: How vulnerable is Antarctica?. Dialogues on Climate Change, 2(1), 8-17.

Fricker, H. A., Galton-Fenzi, B. K., Walker, C. C., Freer, B. I. D., Padman, L., & DeConto, R. (2025). Antarctica in 2025: Drivers of deep uncertainty in projected ice loss. Science, 387(6734), 601-609.

For more information about geoengineering, please see:

Siegert, M., Sevestre, H., Bentley, M. J., Brigham-Grette, J., Burgess, H., Buzzard, S., ... & Truffer, M. (2025). Safeguarding the polar regions from dangerous geoengineering: a critical assessment of proposed concepts and future prospects. Frontiers in Science, 3, 1527393.

If you would like to discuss any of these ideas further, please do not hesitate to contact us:

Prof. Helen Amanda Fricker - hafricker@ucsd.edu

Dr. Bryony Freer - bfreer@ucsd.edu

.webp)